Monday, 29 June 2020

South Africa - Campaign Overview

The history of South Africa from 1877 to 1881 is of a three-cornered struggle between Britain, the Boer Republics and the Zulus. With the exception of a couple of sorties over the frontier, the fighting took place entirely in the Transvaal and Zululand. Combined with the relatively small sizes of the forces involved, this would make a very manageable map campaign. Indeed, I even read once of someone playing the whole thing out on a single large wargame table.

However, my principle of changing as little as possible will be maintained instead. By making just four changes to what happened historically a series of battles can be generated that are both different and, at the same time, familiar enough to make them enjoyable to gamers who know the history of South Africa and those who don't.

Firstly, Chelmsford receives the two battalions that arrived in December 1878 - South Africa was an important strategic location for the British Empire, after all - but after that no more, except for HMS Shah, if she's still afloat.

Secondly, in responding to the British invasion, Cetswayo sends 6000 warriors to face Chelmsford, and the other 20,000 to take on Pearson's column. The battles of Isandhlwana and Nyezane take place as they did historically, but with the Zulu forces exchanged.

Thirdly, Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande and his 4000 men of the Undi corps cross into Natal just as they did in real life, but their target is not Rorke's Drift. Instead they cross the Lower Drift and look for targets down there.

Fourthly, the Transvaal Boers don't revolt in 1880, but in February 1879, whilst Britain is doubly distracted. General Wood's northern column is diverted from Luneberg to deal with them.

These changes allow us to fight historical battles with slightly altered ORBATs, and fictitious battles with the forces from real battles. The result is still a three-cornered war, but one whose outcome is less certain than real life. The British are really up against it in this re-run of history, whilst the Zulus and the Boers both have a real chance of success.

Saturday, 27 June 2020

The Admiralty's orders to Admiral Hornby

Admiralty, London, 6.40 p.m., Jan. 23, to Admiral, Vourla, 11.55 A.M., Jan. 24. " Secret. "

Gallipoli - Letter from Admiral Hornby to Lord Derby

Admiral Hornby

Besika Bay

10 August 1877

Lord Derby

The War Office

London

Sir,

I assume that you think the batteries of the Dardanelles would not prevent the squadron passing into the Sea of Marmora whenever it pleased, and that in passing it might, with small delay and damage, destroy them. In that opinion I concur, but I doubt if you realise what might follow.

If the northern shore of the Dardanelles were occupied by an enemy, I think it very doubtful if we could play any material part; and if the Bosphorus also was under their command, it would be almost impossible. In the latter case, we could not get even the Heraclea coal. In the former, our English supply of coal, our ammunition, and perhaps our food, would in my opinion be stopped. This opinion depends on the topography of the north shore. If you will send for the chart of the Dardanelles, No. 2429, you will see that from three and a half miles below Kilid Bahar to Ak Bashi Imian, six and a half miles above it, an almost continuous cliff overhangs the shore-line, while the Straits close to half a mile in one part, and are never more than two miles wide. An enemy in possession of the peninsula would be sure to put guns on commanding points of those cliffs. All the more if the present batteries, which are a Jleur d'eau, were destroyed. Such guns could not fail to stop transports and colliers, and would be most difficult for men-of-war to silence. We should have to fire at them with considerable elevation. Shots which were a trifle low would lodge harmlessly in the sandstone cliffs ; those a trifle high would fly into the country, without the slightest effect on the gunners except amusement.

It is for these reasons that the possession of the Bulair lines by a strong and friendly force seems to every one here to be imperative, if now, or hereafter, you should want to act at Constantinople. The Turks are making progress with them ; but they are unarmed, not garrisoned, and the garrison that would be sent to them in case of reverse would probably be part of a beaten and dispirited force. Is it wise to risk our vital interests in such hands ? The Russians take advantage of being at war to destroy the Sulina navigation, ' for strategical purposes.' Are we to have no strategical purposes' because we are a neutral? I think even Freeman, Gladstone, & Co. would not hear unmoved that the Dardanelles were closed; but when they are closed, it will be too late to act. Now, I believe there is time to prevent it, and for that reason I write. I want to see 10,000 British troops occupying Gallipoli in concert with the Turks; and Mr Layard misinforms me, if the Turks would not ask for, and welcome, such an occupation.

Yours faithfully

Afghanistan - The British Indian Army

The best officers would want to see action, and this meant service in the Northwest Frontier with the Bengal Army. Nobody wanted garrison duty in a remote and inhospitable station. So, whilst the leadership of the regiments most likely to see combat was excellent, those of the units that would make up the reserve was often questionable.

Tuesday, 16 June 2020

William Morris on the Eastern Question

To the Working-Men of England

Friends and fellow-citizens

There is danger of war; bestir yourselves to face that danger: if you go to sleep, saying we do not understand it, and the danger is far off, you may wake and find the evil fallen upon you, for even now it is at the door. Take heed in time and consider it well, for a hard matter it will be for most of us to bear war-taxes, war-prices, war-losses of wealth and work and friends and kindred: we shall pay heavily, and you, friends of the working classes, will pay the heaviest.

And what shall we buy at this heavy price? Will it be glory, and wealth and peace for those that come after us? Alas! no; for these are the gains of a just war; but if we wage the unjust war that fools and cowards are bidding us wage today, our loss of wealth will buy us fresh losses of wealth, our loss of work will buy us loss of hope, our loss of friends and kindred will buy us enemies from father to son.

An unjust war, I say: for do not be deceived! If we go to war with Russia now, it will not be to punish her for evil deeds done, or to hinder her from evil deeds hereafter, but to put down just insurrection against the thieves and murderers of Turkey; to stir up a faint pleasure in the hearts of the do-nothing fools that cry out without meaning for a ‘spirited foreign policy'; to guard our well-beloved rule in India from the coward fear of an invasion that may happen a hundred years hence – or never; to exhibit our army and navy once more before the wondering eyes of Europe; to give a little hope to our holders of Turkish bonds: Working-men of England, which of these things do you think worth starving for, worth dying for? Do all of them rolled into one make that body of English Interests we have heard of lately?

And who are they who flaunt in our faces the banner inscribed on one side English Interests, and on the other Russian Misdeeds? Who are they that are leading us into war? Let us look at these saviours of England’s honour, these champions of Poland, these scourges of Russia’s iniquities! Do you know them? Greedy gamblers on the Stock Exchange, idle officers of the army and navy (poor fellows!), worn-out mockers of the Clubs, desperate purveyors of exciting war-news for the comfortable breakfast tables of those who have nothing to lose by war, and lastly, in the place of honour, the Tory Rump, that we fools, weary of peace, reason and justice, chose at the last election to ‘represent’ us: and over all their captain, the ancient place-hunter, who, having at last climbed into an Earl’s chair, grins down thence into the anxious face of England, while his empty heart and shifty head is compassing the stroke that will bring on our destruction perhaps, our confusion certainly: O shame and double shame, if we march under such a leadership as this in an unjust war against a people who are not our enemies, against Europe, against freedom, against nature, against the hope of the world.

Working-men of England, one word of warning yet: I doubt if you know the bitterness of hatred against freedom and progress that lies at the hearts of a certain part of the richer classes in this country: their newspapers veil it in a kind of decent language; but do but hear them talking among themselves, as I have often, and I know not whether scorn or anger would prevail in you at their folly and insolence: these men cannot speak of your order, of its aims, of its leaders without a sneer or an insult: these men, if they had the power (may England perish rather), would thwart your just aspirations, would silence you, would deliver you bound hand and foot for ever to irresponsible capital – and these men, I say it deliberately, are the heart and soul of the party that is driving us to an unjust war: can the Russian people be your enemies or mine like these men are, who are the enemies of all justice? They can harm us but little now, but if war comes, unjust war, with all its confusion and anger, who shall say what their power may be, what step backward we may make? Fellow-citizens, look to it, and if you have any wrongs to be redressed, if you cherish your most worthy hope of raising your whole order peacefully and solidly, if you thirst for leisure and knowledge, if you long to lessen those inequalities which have been our stumbling-block since the beginning of the world, then cast aside sloth and cry out against an unjust war, and urge us of the Middle Classes to do no less, so that we may all protest solemnly and perseveringly against our being dragged (and who knows for why?) into an unjust war, in which, if we are victorious, we shall win shame, loss and rebuke; and if we are overpowered – what then?

Working-men of England: I do not believe that in the face of your strenuous opposition, the opposition of those men whom war most concerns, any English Government will be so mad as to trap England and Europe into an unjust war.

A Lover of Justice

11 May 1877

Saturday, 13 June 2020

The Mukta Mutiny - Betraying the Queen's salt

Thursday, 11 June 2020

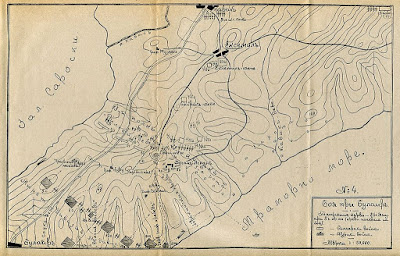

Gallipoli - The Maps

Prologue: The Battle of Pacocha

https://web.archive.org/web/20040803142718/http://members.lycos.co.uk/Juan39/BATTLE_OF_PACOCHA.html

-

Austria-Hungary's slice of the spoils of 1878 was the province of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Taking it should have been straight forward...

-

On 29 May 1877 an indecisive naval battle was fought off the coast of Peru. The Peruvian armoured monitor Huascar had been seized ...

-

You can't talk about wargaming without talking about rules, and you can't talk about wargames rules without getting into, sometimes ...

.jpg)